Ramda vs Vanilla JS

October 02, 2019

- Introduction

- CodeSandbox

- Safely accessing deeply nested values

- Data transformations

- Conditionals

- Merging objects

- Ranges generation

- Handling side effects while staying functional

- Currying and partial application in one

- Summary

This is a list of functions linked to the the section with usage:

- propOr, prop, map, cond, either, equals, always, T, __, mergeDeepWith, concat, range, pipe, sum, tap, lt (lessThan), curry, when

Please reach out to the documentation to read up on a detailed explanation of each function.

Introduction

My intention is to show some examples of usage of the Ramda library and, since there are some relatively similar implementations in Vanilla JS, to better express what is happening with the concise functional code of Ramda..

I’m not a proponent of using Ramda everywhere, just to be clear. I don’t like how people try to be consistent and use one lib wherever they can. Instead, I prefer to consistently produce readable code, using any means necessary.

JS is not a bad language especially with the awesome work that's been put into it over the past few years and since the release of ES6. If you're working on a codebase with other developers, think about tradeoffs before using code like this that could be done in vanillla JS. pic.twitter.com/WHNPcyNmR2

— Nader Dabit (@dabit3) August 1, 2019

I don’t want to explain how functions work or judge which approach is better than the other. I will rather show examples in context and compare them with the Vanilla JS implementation if possible.

CodeSandbox

To support a better reading experience you get access to all of the code from the article which you can change, fork and test - there are unit tests for each and every case. Moreover, you can find a tutorial on how to consume CodeSanboxes here.

Safely accessing deeply nested values

It’s always been tedious to reach nested data in JS objects. Everybody has been waiting for optional chaining for a long time now and happily we’re getting there.

I first saw it in Kotlin while working on native Android apps, and it seems that the syntax will be similar:

const includes = app?.data?.listOfItems?.includes("something")Until then (or until you use this) you could either use one of the existing libraries or Vanilla JS:

const includesJS = obj => !!obj &&

!!obj.data &&

!!obj.data.listOfItems &&

obj.data.listOfItems.includes('something')const includesRamda = obj => R.pathOr([], ['data', 'listOfItems'], obj).includes('something')Data transformation

Let’s complicate this example . Not only do we have to access the nested object but also map over the results.

It may be the case that you don’t have to do any data transformations before rendering, because the fetched data fully matches the client’s needs. But things don’t always go so smoothly. Especially if you work with legacy code, or you have just been involved in rapid prototyping for a startup, there will definitely be a discrepancy between how your data scheme looks on the backend and what the frontend needs.

Imagine you have an object which has a list of items that you want to map to something else, which defaults to an empty array if something is missing:

const favorites = {

movies: [

{

name: 'The Shawshank Redemption',

views: 264726342,

},

{

name: 'The Godfather',

views: 264726343,

},

],

otherProps: {},

}You’re using untyped JS, but if it was TypeScript, types would tell you that data at all levels are optional:

interface Movie = {

name: string,

views: number,

}

interface Favorites = {

movies?: Array<Movie>,

}

const enhanceFavoritesTs = (favs?: Favorites): EnhancedFavoritesAnd maybe if we were completely sure that none of our data would be missing we could just do it in the following way:

export const enhanceFavoritesTs = (favs: Favorites): EnhancedFavorites =>

favs.movies.map(({ name, views }) => ({

name,

views,

value: `${name} has been viewed ${views}`,

}))But instead we don’t know anything about types and we have to assume that it can crash at any time when accessing the nested values. And here are just 3 examples of how this case can be handled:

You can start by implementing a solution with a ternary operator. You will quickly notice, however, that you can’t pull this off without nesting another ternary operator to ensure that both favs and movies are not undefined:

export const enhanceFavoritesTernary = favs =>

favs

? favs.movies

? favs.movies.map(({ name, views }) => ({

name,

views,

value: `${name} has been viewed ${views}`,

}))

: []

: []You decide to ditch the ternary operator by following your gut feeling, or if the linter configuration was strict enough, or maybe because of your colleague’s advice during code review… anyways, now you use a bunch of if-else statements:

export const enhanceFavoritesIfs = favs => {

if (favs) {

if (favs.movies) {

return favs.movies.map(({ name, views }) => ({

name,

views,

value: `${name} has been viewed ${views}`,

}))

} else {

return []

}

} else {

return []

}

}You are new to the codebase, just joined the project and didn’t know that there is already Ramda onboard, why not give it a try? This is the implementation with Ramda.js:

export const enhanceFavoritesRamda = R.pipe(

R.propOr([], 'movies'),

R.map(({ name, views }) => ({

name,

views,

value: `${name} has been viewed ${views}`,

})),

)It differs very much from the Vanilla JS implementations. No fat arrow? No parameter? Well, it’s created by R.pipe behind the scenes. The function takes whatever you provide it with and implicitly passes it along to the first function. It executes from left to right (or top-down here): it first accesses the ‘movies’ property and defaults to an empty array if needed, and then maps to what we need.

One thing can be noticed at this point - Ramda allows for the easy composition of functions.

Conditionals

You simply want to map one string to another, depending on what the string is. It might be that there is a business need to rename types of an entity, and there’s no way that the change would be done on the backend:

Implementation with if statements:

export const mappingIfs = type => {

if (type === 'table' || type === 'chair') {

return 'Furniture'

}

if (type === 'trousers') {

return 'Cloths'

}

if (type === 'house') {

return 'Real Estate'

}

return 'Unknown'

}Implementation with switch:

export const mappingSwitch = type => {

switch (type) {

case 'table':

return 'Furniture'

case 'chair':

return 'Furniture'

case 'trousers':

return 'Cloths'

case 'house':

return 'Real Estate'

default:

return 'Unknown'

}

}Implementation with Ramda’s cond and equals, which encapsulates if/else statements:

export const mappingRamda = R.cond([

[R.either(R.equals('chair'), R.equals('table')), R.always('Furniture')],

[R.equals('trousers'), R.always('Cloths')],

[R.equals('house'), R.always('Real Estate')],

[R.T, R.always('Unknown')],

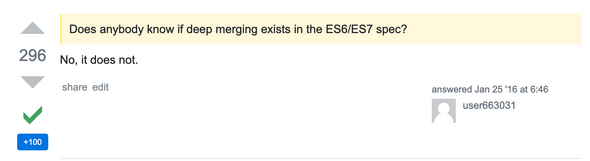

])Merging objects

Imagine you have to update an object with some new properties. Let’s say you’re using Redux and you have a pretty complex state object which stores various information about your app. It looks like this:

Well, we have to find another way to handle it.

const state = {

cart: {

items: {

variousItems: [

{

id: 1,

},

],

differentItems: [

{

id: 1,

},

{

id: 2,

},

],

},

},

}And you want to update your state with:

const update = {

cart: {

differentItems: [

{ id: 2, total: 100, }, { id: 3, total: 1000, }, ],

},

}There is just one change here, two new items are added to one of the nested lists.

Solution with Vanilla JS:

const output = {

cart: {

items: {

variousItems: state.cart.items.variousItems,

differentItems: [

...state.cart.items.differentItems,

...update.cart.items.differentItems,

],

},

},

}Solution with Ramda:

const output = R.mergeDeepWith(R.concat, state, update)The problem with the Vanilla JS implementation is that it will only work for that particular case. If we add another property to the ‘update’ object, our implementation will have to be updated too.

A caveat for one case is an advantage for another. The Ramda implementation will execute deep merge for the whole object, whereas you may want to choose where to apply the change instead.

Ranges generation

You need a list of numbers going from a to b. Like range(30, 32) yields [30, 31, 32]. Unless you implement your own solution for JS you don’t have a utility to do this. While there are number of ways to implement it in vanilla js, one can choose to use a range from Ramda:

R.range(30, 32)Handling side effects and not leaving a chain

Handling UI is inherently connected with side effects. Either from user interactions with a UI, or when fetching data and depending on the response.

You can use R.when to fire-and-forget any function

(just be careful with interpreting gt, which stands for greater than https://github.com/ramda/ramda/issues/1497)

export const sideEffectRamda = (date, navigate) =>

R.pipe(

R.map(R.prop('amount')),

R.sum(),

R.tap(console.log),

R.when(R.lt(35), () => navigate('success-page')),

)(date)export const sideEffectJs = (date, navigate) => {

const sum = date

.map(element => element.amount)

.reduce((prev, next) => +prev + +next, 0)

console.log(sum)

if (sum > 35) {

navigate('success-page')

}

}Currying and partial application in one

Currying and partial application is achieved with Ramda with a single operator named curry. This is basically an all-in-one solution which gives you the flexibility to apply any number of whichever arguments you choose.

For instance, if you have a function which takes 3 arguments, you can apply the second and third and get a function which gets the first as a result (and that function will already have the second and third arguments in its closure)

const example = R.curry((first, second, third) => {})

const onlyFirst = example(R.__, second, third)

const result2 = onlyFirst(first)

// but also

const result1 = example(first, second, third)

// and so onOne of the practical usages of this operator is to apply an argument which is the same for more than one function invocation. So instead of:

const sum1 = sumUp(elements, "wooden")

const sum1 = sumUp(elements, "metal")

const sum1 = sumUp(elements, "ceramic")You can do the following and avoid repetition:

const sumUpElements = sumUp(elements)

const sum1 = sumUpElements("wooden")

const sum1 = sumUpElements("metal")

const sum1 = sumUpElements("ceramic")Let’s take a real life example:

The function itself in Ramda:

const sumUpRamda = R.curry((element, type) =>

(element || [])

.filter(element => element.type === type)

.map(element => element.amount)

.reduce((prev, next) => +prev + +next, 0),

)We can try a simple Vanilla JS implementation, and compare the two:

const sumUpJS = element => type =>

(element || [])

.filter(element => element.type === type)

.map(element => element.amount)

.reduce((prev, next) => +prev + +next, 0)Our input:

const elementList = [

{ type: 'requested', amount: 10 },

{ type: 'requested', amount: 20 },

{ type: 'unknows', amount: 20 },

]Vanilla JS

There’s not much flexibility with the JS implementation:

-

either supply the arguments one by one:

const sumJS = sumUpJS(elementList)('requested') - or supply the first argument, name the next function, and then call it later with the second argument:

const sumUpElements = sumUpJS(elementList)

const sum = sumUpElements('requested')Ramda

We can provide all of the arguments at once:

const sum1 = sumUpRamda(elementList, 'requested')First argument, name the function, then the second later on:

const sumUpElements = sumUpRamda(elementList)

const sum2 = sumUpElements('requested')This is really different, we can provide the second argument, which creates the function that takes the first from the initial function.

const sumUpTypeRequested = sumUpRamda(R.__, 'requested')

const sum3 = sumUpTypeRequested(elementList)Obviously, the number of possibilities grows with the number of arguments.

Summary

Even though the goal of this post isn’t to judge, Ramda enables all sorts of functional patterns and comes with a set of handy functions. It doesn’t come without a price: a brand new syntax.

Join the Newsletter

Written by Bart Widlarz who works remotely in software development as a developer and leader. CONTACT ME